Cast in Time: The Legacy of Sport Casting in Chicago

By Jim Dorr

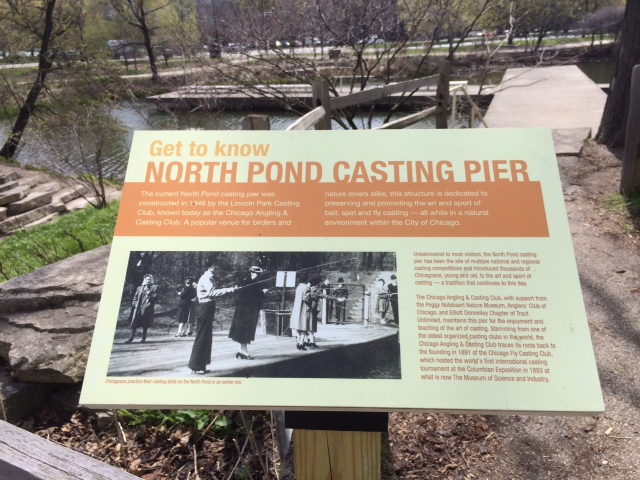

At the southern end of the North Lagoon in Chicago’s Lincoln Park, directly west of the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum, lies a 150 by 120 foot cement pier in approximately the shape of a cross. Few who drive by on Fullerton or Stockton Drive, or who stroll by on Lincoln Park’s paths, or who use the piers benches to sunbathe, bird watch or as a place to appreciate the serenity of nature amid the high-rises surrounding Lincoln Park in the dusk of the evening are aware of the purpose of the pier or the Chicago legacy it represents.

Every legacy has a beginning; this begins during the event that catapulted Chicago onto the world stage – the World’s Fair of 1893. It was in the White City that the first “Open to the World Scientific Angling Tournament” was held, launching Chicago as the center of the universe of the sport of tournament casting – a sport that for decades was a means of recreation and competition for many Chicagoans and that drew thousands of spectators to Chicago’s parks and lagoons for national championships. And a sport that not only helped to transform all aspects of angling equipment and technique, but also played a significant role in promoting the most lasting heritage of all – the conservation of our precious resources.

As with other aspects of angling, casting contests originated in England where informal groups got together for competition. Likewise in the United States such contests began to take place informally, largely on the east coast. These contests initially were conducted with fly rods and were judged primarily on distance. In 1884, however, Dr. James Henshall, a noted author and angler whose 1881 Book of the Black Bass helped revolutionize sport fishing in America, developed an event featuring bait casting that placed a premium on accuracy as well as distance. Competitions were still conducted informally. Then in 1891, the first casting club in America – the Chicago Fly Casting Club – was founded by a group that included Charles Antoine, co-owner of the famed Von Lengerke & Antoine (later Abercrombie & Fitch) sporting goods store that had opened earlier that year. The club held meetings in the back of the VL&A store on Wabash Street in downtown Chicago. It was under Antoine’s leadership at those meetings that “[t]his grandest of all angling tournaments” was organized (The Sportsman’s Journal, Sept 30, 1893).

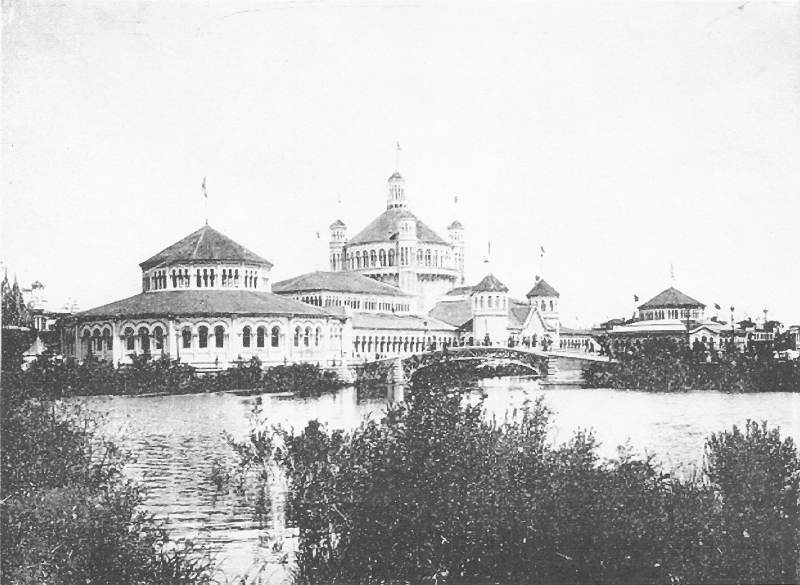

The venue for the tournament was indeed grand. Much has been written about the wonders of the White City, but little has been noted of the portions of the Fair devoted to angling and our fisheries. Yet the Spanish-Romanesque Fish and Fisheries Building, one of the ten principle buildings of the Fair, was widely regarded as one of the fair’s most beautiful.

Fish & Fisheries Building as photographed from the Wooded Island

It was designed by architect Henry Ives Cobb, who also designed the Newberry Library and was responsible for the master plan of the University of Chicago. The rectangular main structure facing south contained international and state exhibits, commercial fisheries, scientific investigations and fish culture. The polygonal pavilion on the east end of the building housed a 140,000 thousand gallon aquarium.

The Angling Pavilion on the west mirrored the aquarium on the east in outward appearance. The same Dr. James A Henshall who had developed the new format for bait casting contests was the chief of the Angling Pavilion, the angling portion of which shared space with some state exhibits. In a speech to the American Fisheries Society at the Fair on July 15, 1893, Henshall described the various angling items to be seen – the latest in rods, reels, lures, lines and other tackle, trophies and trophy fish and historical displays. He summed up: “While the exhibit is small, it is a very characteristic exhibit of angling goods which are manufactured today, and while it fills the bill … it does not fill the building.”

The Angling Pavilion certainly “filled the bill” from the angler’s perspective. Improvements in and increased affordability of fishing tackle, much of which was exhibited in the Angling Pavilion, had led to an increased popularity of sport fishing. The split bamboo rod had been developed by Pennsylvania rod maker Samuel Phillippi in the mid 19th century and famous rod makers such as H. L. Leonard were perfecting the art. Vermont rod maker and tackle purveyor Charles Orvis developed a reel that became the prototype for modern fly fishing reels. Bait casting was beginning to gain on fly fishing in popularity following the invention of bait casting reels. High-grade silk lines improved casting ease, distance and accuracy. And the terminal tackle used to catch fish was also the subject of experimentation and popularization. A whole industry had developed in upstate New York crafting metal lures of outstanding beauty and intricate detail for both fly and bait casting. The father of American dry fly fishing, Theodore Gordon, had begun writing about success in designing artificial flies to match insects on the water’s surface. Mary Orvis Marbury, daughter of Charles Orvis, published her classic Favorite Flies and Their Histories, which became the American standard for wet (underwater) fly patterns. Her exhibit of flies and fishing pictures was one of the most popular of the Exposition.

Just as the World’s Fair became known to have fostered an unprecedented age of consumer orientation it was also the harbinger of an unparalleled era in popularity of angling and an attendant explosive growth of angling related products. With that popularity came an increased interest in the techniques of fishing, including the art and science of casting. There too the Fair made its lasting contribution with its “Open to the World” casting tournament.

The tournament was held on two successive days beginning on Sportsmen’s Day at the Fair – September 21. Events were held for experts and amateurs in both fly casting and bait casting. “Expert” participants came from all parts of the country, but many “amateurs” lined up that first morning to register and receive their numbered cards signifying their order in their event.

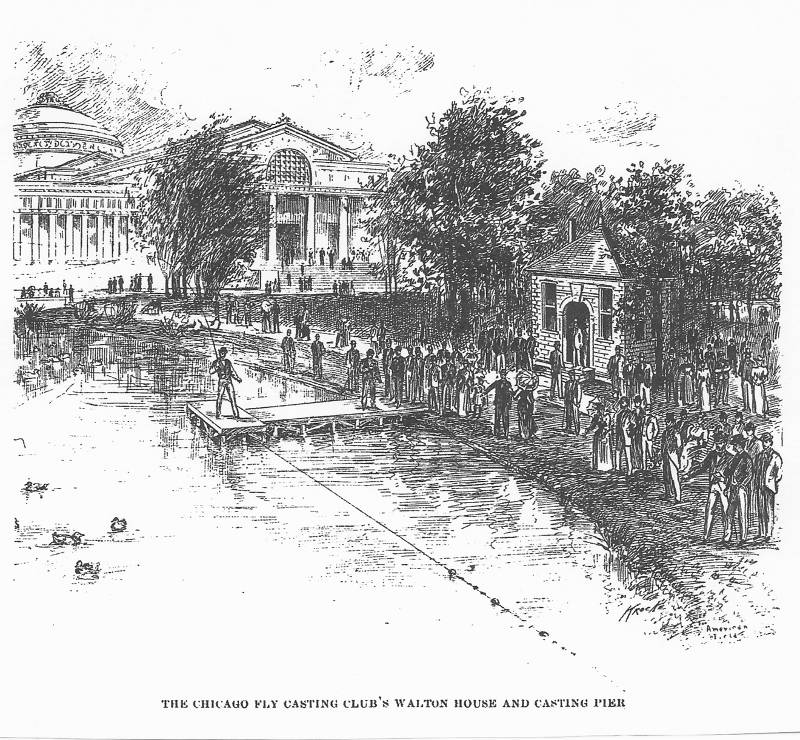

The fly casting competition was held on the shore of the North Pond, near the Palace of Fine Arts (now the Museum of Science and Industry). There, in honor of the 300th anniversary of the birth of Isaac Walton, the Chicago Fly Casting club had erected a replica of Isaac Walton’s fishing house on the River Dove made famous in his The Compleat Angler, first published in 1653. To anglers of the time and continuing through today, Walton is considered to be the patron saint of angling, representing through his prose and verse the highest ideals of angling, sportsmanship and conservation. The Isaac Walton Lodge had served as a gathering place for anglers throughout the time of the Fair – a place to exchange fishing tales and to practice casting on the pier erected on the pond in front of the Lodge. Now, the Lodge was tournament headquarters and the pier the site of the fly casting portion of the tournament.

The Chicago Fly Casting Club’s Walton House and Casting Pier

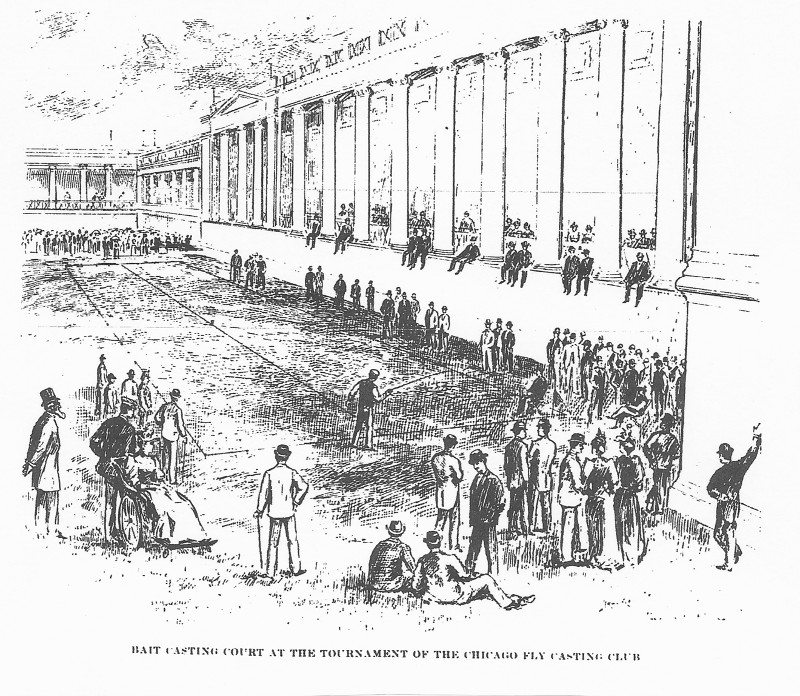

For the first time, the fly casting competition was linked definitively to accuracy as well as distance. In the accuracy events, six inch red, white and blue spheres were anchored at stated distances triangularly, depending on the expertise required for the event. Expert, amateur and “light rod for accuracy and delicacy” events were held. Fly casting for distance events were also held, measured on a marked buoy line extending out from the pier. The bait casting competition was held on a 30 ft wide by 200 ft long court on the lawn north of the Palace of Fine Arts. That contest also required accuracy as well as distance, with demerits being issued depending on the distance the cast ½ ounce weight deviated from a tape running the entire length of the court.

Bait Casting Court at the Tournament of the Chicago Fly Casting Club

Humorous events occurred along with feats of accuracy, power and grace during the bait casting tournament. One such event was recorded in the Sept 30, 1893 Sportsman’s Journal report of the proceeding:

“Another cast sailed to the right of the court, struck the Grecian columns of the Art Palace with sufficient force to indent the leaden weight and, caroming off, lassooed (sic) a lady spectator’s bonnet with loop of his line, as it settled down. After extricating the line from the frills and flowers of this floral headgear he reeled in and tried it again.”

The emphasis on accuracy and, in some events, delicacy underlies the meaning of the use of the word “scientific” in connection with the tournament and perhaps helps explain the fame that this tournament garnered. Although the “tournament work” of casting long distance was appreciated, the most popular and educational events for the angler were those that required accuracy and delicacy at distances that were more in line with those anglers experience while fishing.

It is perhaps partly for this reason that the popularity of sport casting exploded in the years following the World’s Fair. The San Francisco Fly Casting Club became the second casting club to formally be formed, but in no time clubs, both formal and informal, were springing up all across the country in cities big and small, from New York City to Kalamazoo and Racine. Chicago remained the center of tournament casting, however. Following the Exposition, three more Scientific Angling World Championships were held there, in 1897, 1900 and 1905, before the formation of the National Association of Scientific Angling clubs (N.A.S.A.C.) in 1906 resulted in yearly national competitions being held in different venues, including many in Chicago, over the next half century. Chicago’s preeminence in the sport is exemplified by the fact that 7 different Chicagoans won 14 out of the first 15 “All- Round Champion of the United States” titles of the N.A.S.A.C. It was not until 1932 that a club from other than Chicago won the annual club championship.

The sport of casting was not limited to experts casting in national tournaments. By the end of the first decade of the 20th century additional casting clubs had been formed throughout the Chicago area, most notably the Illinois Casting club, the Anglers Casting Club and the Lincoln Park Casting Club . Casters practiced after a day of work much as one might go to a driving range today, although seemingly with a good deal more camaraderie. On any given weekend in the summer, casting events were held by one or more of these clubs in Garfield Park, Washington Park, Douglas Park, Lincoln Park or other venues throughout the city. These events became a social focus for gatherings on weekend afternoons while participants practiced, played casting games or competed with each other or with other clubs. Young and old participated, both male and female. Here is but an example of one such afternoon, from photos taken by the Chicago Daily News in 1905:

Tournaments and other events during the season were regularly highlighted in the newspapers of the day by outdoors columnists such as the self described “pillar of piscatorial perspicacity” Larry St. John in his popular Woods & Waters column in the Chicago Daily Tribune. And the public was interested. During their height of popularity, more than 20,000 people would gather over a weekend to watch contests of particular note in one of Chicago’s parks.

The casting participants came from all walks of life and exemplified the “scientific” and entrepreneurial spirit of the period. Many were fishermen themselves who took up casting as a means of improving their skills. Others were primarily interested in casting for casting sake. Regardless, many became known for their creative contributions to both casting and fishing in the ensuing years. And here again, Chicagoans very much led the way. J.M. Clark, a charter member of the Chicago Fly Casting Club and second place finisher in one of bait casting events at the Fair, is widely credited with being the first to design the short bait casting rod which became prevalent in both casting and angling. He also is credited with being a leader in developing the “Chicago Style” of casting. E. R. Letterman designed the first wooden weights for casting contests, stamping them C.F.C.C. until the founding of N.A. S. A.C. in 1906. He became so overwhelmed by the demand for these weights, which he made in his den, that he developed an aluminum weight that was much easier to commercially manufacture to necessary rigorous standards. It became the main stay of tournament casting for many years.

Letterman CFCC Casting Weight Circa 1905

Bill Jamison was a printer at the Chicago tribune and avid fisherman at the time he saw his first casting tournament in 1903 and was hooked. As he put it, he would “rather fish than eat and rather do tournament casting than fish.” By 1905 he had not only won events in the first tournament he entered, but also started his own tackle company, located first in his home and then at various addresses in Chicago. He went on to found the Angler’s Casting Club of Chicago in 1908 and to set several club and national records over the years. His tackle company grew to rival all the major tackle companies of the day before his death in 1926. His many inventive products included the fly rod Coaxer, the first floating fly rod lure.

William Stanley, who founded the Illinois Casting Club in Washington Park 1904 to make casting more accessible to members living on the south side of Chicago and was later a 4 time National All-Round casting champion, designed and sold his Perfection Weedless Hook and related products from his factory on East 55th Street. His close friendship with Illinois and Lincoln Park Casting Club member Jack Welch, who received 28 patents for rods, reels, and lures throughout his career, resulted in arrangements with Welch’s employer James Heddon’s Sons to manufacture the well known Heddon Stanley Lure.

Will Dilg and Call McCarthy, who won the All-Round National Casting Championships in 1914, 1916 and 1921, were two other prominent Chicago tournament casters who devoted their creative attentions to developing the “Mississippi” style and patterns of bass bug that popularized that means of fishing for bass with a fly rod during the late teens into the 1920s. McCarthy sold his Callmac floating bugs under his own name before transferring the rights to the South Bend Bait Company, which continued to sell them into the 1950s. Designed by B.F. Wilder and promoted by Will Dilg, the Heddon Wilder-Dilg floating fly rod minnow launched in 1923 became another popular fly rod lure for many decades.

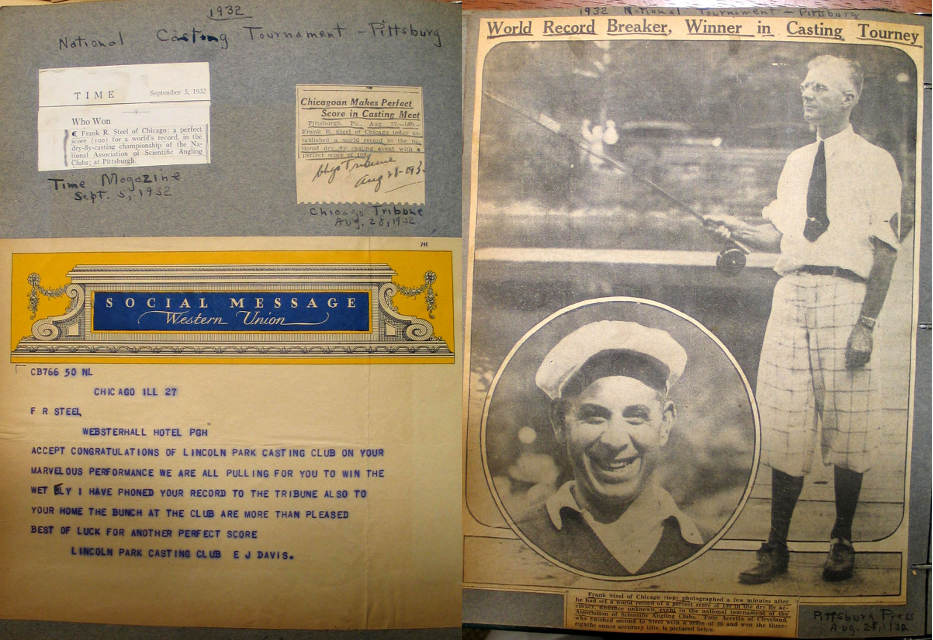

Frank Steel, a member of the Lincoln Park Casting Club, continued the “scientific angling” tradition in later years. He became the only person to ever post a perfect score in a national or state dry fly competition when he won that competition at the national event in Pittsburg in 1932.

From the Steel Family Scrapbook

An avid angler, he also set a record for largest Chinook salmon ever caught. His scientific bent led him to devote many years to the study of fish habit, resulting in a method for correlating the habits of salmon and trout to water temperature. He imparted his knowledge of casting and fishing to others through careful instruction on the pier of the Lincoln Park Casting Club as well as through books and his position as editor of Fishing Tackle Digest. Among his pupils were: future multiple national champion George Applegren; Jim Chapralis, who on a whim entered and won the distance fly casting contest with borrowed equipment at the famed Bois de Boulogne outside Paris while serving in the military in the mid 1950s; and renowned angler, author and artist Ernest Schwiebert.

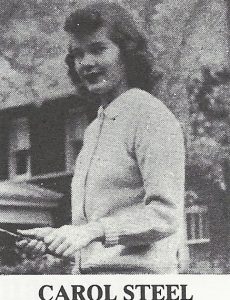

Another of Frank Steel’s pupils was his daughter, Carol, who also cast in tournaments for the Lincoln Park Casting Club.

Carol Steel

During the mid 1940s she carried on an intense rivalry with another young female caster from New Jersey by the name of Joan Salvato. As Carol would later describe it: “she won some and I won some.” In all, Carol would win three National fly Casting championships before and while attending the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University.

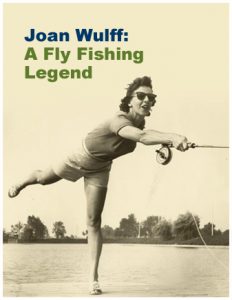

Carol’s rival, Joan Salvato Wulff, won her first fly casting contest as a teenager on the Lincoln Park casting pier in Chicago in 1943. She went on to become perhaps the greatest fly caster of all time, male or female, and continues to this day to offer instruction at the fly fishing school she and her husband Lee founded in the Catskills.

Joan Wulff

Carol Steel and Joan Salvato Wulff are but two examples of the fact that casting is an egalitarian sport. The competition in casting did not end within the sexes; it existed between them as well. As reported in Field & Stream in November 1905, the Ladies Bait Casting Club of Kalamazoo, Michigan boasted that any five of its members would “beat any team of five men from any club in this country.”

It is not known whether any team of men was brave enough to take them up on it. What is known is that Joan Salvato Wulff regularly defeated men in competitions throughout the country, including a National Distance Casting Event against an all-male field.

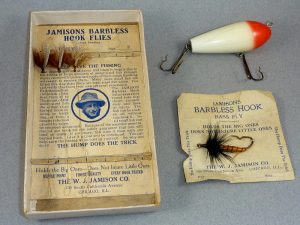

Although the contributions Chicago casters made to their sport were many, it is the contribution they made to all of us through their dedication to conservation that is the most lasting. A founding purpose of the Chicago Fly Casting club in 1891 was to “assist in the protection and propagation of game fish.” As time went by the members of all of the Chicago area casting clubs became more and more concerned about the effects of pollution, overfishing and related problems on the environment in general and the fish population in particular. They sought to find ways to answer a question that was being asked nationwide by conservation minded anglers: “What shall we do to save the fishing?” One of them, Bill Jamison, sought to help do so through the tackle he manufactured. To that end he designed and patented a barbless hook. That design replaced the barb on the hook with a hump – and “The Hump Does The Trick” and “Holds The Big Ones – Does Not Injure The Little Ones” became the watchwords to “help save the fishing.” Ahead of his day, he pioneered the production of a movie to be disseminated to fishing clubs to demonstrate the effectiveness and humanity of the barbless hook.

Among the concerned anglers, Will Dilg, long time member of the Chicago Fly Casting club, emerged as the leader. On January 14, 1922 he convened a meeting at the Chicago Athletic Club of a group of 54 Chicago anglers, over 40 of whom belonged to one of the four major Chicago casting clubs. Charles Antoine, the V L & A owner and C.F.C.C. founder was there. So was Bill Jamison. So was Preston Bradley, founder of the Peoples Church of Chicago – and anglers from many other walks of life, all interested in doing something to save the fish. That day they formed the Isaac Walton League of America, the first grassroots conservation organization, in order to advocate for ethical angling, better fish laws, clean water and other measures to protect and preserve our outdoor resources. Will Dilg became its first President. Two years later, the Isaac Walton League had over 100,000 members nationwide and Will Dilg had successfully advocated in Washington for the establishment of the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge on his beloved Mississippi River. The League continues to this day as an advocate for the principles articulated by its 54 Chicago founders more than 90 years ago.

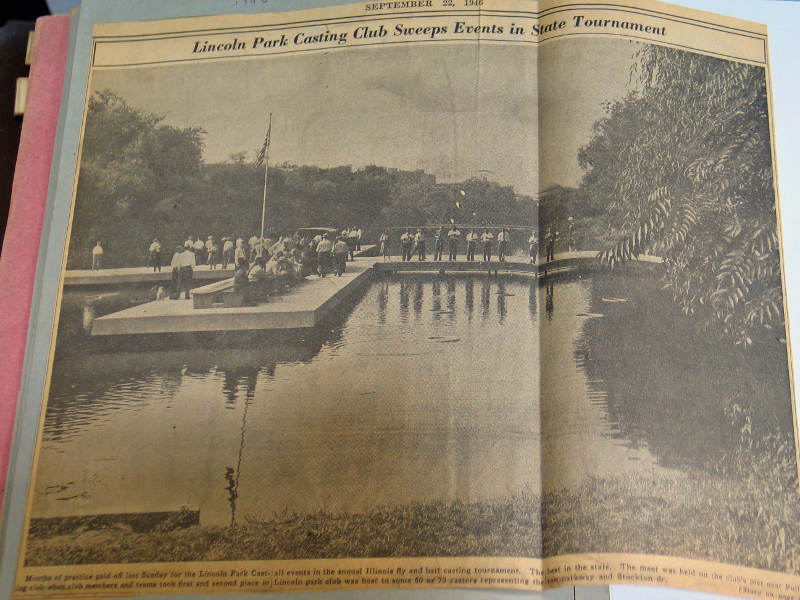

In 1946, the Lincoln Park Casting Club erected a new concrete pier to replace the old wooden pier that had seen better days. The Crown family donated the concrete for the pier in order to provide a more lasting venue for future generations. It proved its merit immediately as this Tribune photograph from the fall of that year attests. It has been the site of multiple national, state and local competitions since then.

The pier today is a testament to the legacy it represents.

But it is more than that. It is a present day resource for the enjoyment and teaching of the sport of bait, spin and fly casting. Rings are set out in the water in season much as they were many decades ago. The Chicago Angling and Casting Club, the successor to the Lincoln Park casting club, still holds occasional tournaments there. It is often used for professional fly casting instruction. Most importantly it is a resource for urban residents of all ages, but most especially children, to learn how to cast in a beautiful and natural setting. Free casting lessons are provided through the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum. And, of course, it can simply be a place to come to practice, adding your cast to the “casts in time” that are Chicago sport casting.

Copyright © 2016 by Jim Dorr All rights reserved. This story or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the author, Jim Dorr.